The year 2020 marks twenty years since EASI founder William Coleman began to identify, value and develop ecological assets on private lands.

In 1999 the New York Times interviewed Coleman about the first-of-its-kind program he was managing, then for the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), understand the eco-asset value of legacy properties owned by U.S. energy companies — properties that were about to be sold or donated for conservation purposes.

“The energy boom of the 1980s was over,” Coleman recalls. “Holding land that would probably never be needed for power plant development showed up as a liability on company books.”

In many cases those lands were some of the most remote and ecologically important properties in America. Companies hoped to derive some level of value beyond a straight sale by, for example, donating the properties to glean the public relations value of committing lands for public enjoyment and conservation.

Coleman believed that these lands held far more value than companies realized. He considered the rapidly diversifying marketplace for ecological assets such as wetlands credits, stream credits, species credits and carbon credits. As early as 1990 these ‘mitigation credits’ were demonstrating significant monetary value in their individual market niches. Nobody had thought about integrating those values into a single expression of property net worth.

“Even the donation of a property could earn a landowner additional tax-related value,” Coleman reasoned, “if ecological assets were built in to the equation.”

The Times wanted to find out how this idea worked. Their January 18, 1999 article wrote:

“…the ultimate goal of this approach is to translate a property’s intangible environmental value into a very tangible financial value. In that way, Coleman says, the value of utilities’ most ecologically-important land holdings would be increased – perhaps significantly – which likely would satisfy utility shareholders, while at the same time satisfying environmentalists who want environmentally sensitive land to remain undisturbed.”

“The Times article nailed it,” according to Coleman.

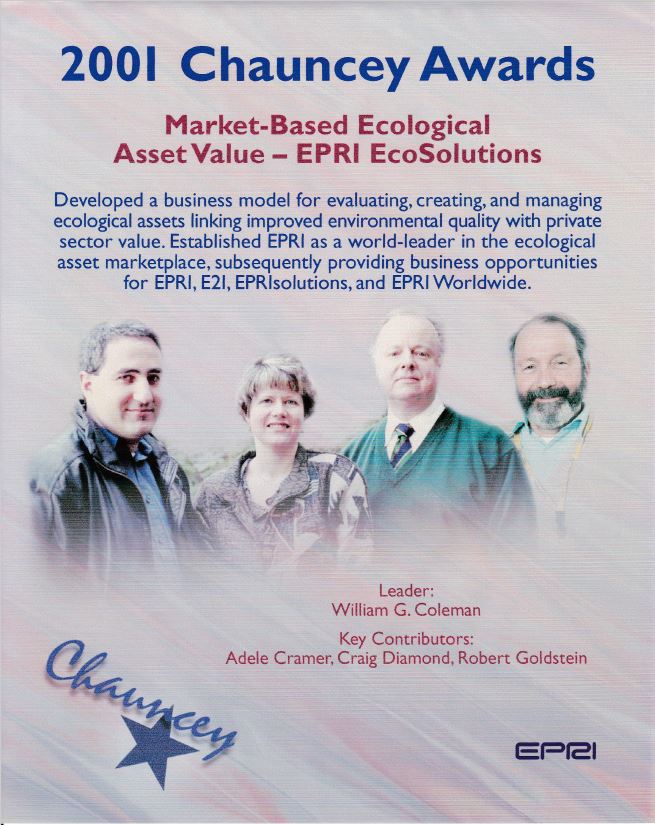

In 2001 EPRI itself acknowledged the success of this idea by awarding Coleman and his team a coveted “Chauncey Award”, the company’s highest annual recognition (named for EPRI founder Chauncey Starr). The award was for “evaluating, creating, and managing ecological assets linking improved environmental quality with private sector value.”

In 2015 Coleman founded EASI and began to focus exclusively on ecological asset identification, valuation and development. Over the last five years the company has conducted more than thirty studies nationwide. Each project has confirmed that ecological asset value can deliver a combination of land-based revenue, land sales and tax-related values, as well as long term ecological value by conserving those same rural properties for the long term.

“In this case, size doesn’t matter,” Coleman says. “Whether 10,000 acres in Florida ($125 million eco-asset value), 1400 acres near Olympia, Washington ($15M), or 65 acres on San Francisco Bay ($40M), a property can leverage substantial value for its owner. It’s more about location than size…that old real estate mantra.”

Coleman believes that property eco-asset values will soon be a standard component of every land appraisal. “Highest and best use turns out to be about both economic and ecological value,” he says. “We’ve worked with the appraisers to show them how it’s done. The smart companies are already putting our concepts, methods and tools to work for their clients.”

He added with a smile, “The next twenty years will prove this idea beyond a doubt. I intend to be here to see it happen.”